Samraj Project and Design Newsletter - June 2018

URBAN PLANNING MONTHLY

CEDA’s latest report concludes that the housing affordability crisis is here to stay—at least for the next 40 years. Even as cities like Melbourne and Sydney continue to construct record number of housing dwellings, the demand far surpasses the present rate of supply. This month’s issue sheds light on factors that are making it harder for new home buyers to get a good deal.

THE HOUSING AFFORDABILITY CRISIS IN AUSTRALIA

In 2017, Australia is said to be faced with a housing affordability crisis (Mitchell 2017; Salt 2017). Rapidly increasing house prices, since the beginning of this century, have resulted in increasing social, geographical, and generational inequalities when it comes to access and the distribution of this essential resource. This is resulting in a growing number of the populace unable to access safe and affordable housing which is important to the well-being and health of families.

Presently new households are being formed by people arriving in Australia and from residents starting to live independently. The net influx of Net Overseas Migration (NOM) settling in NSW (almost all of whom located in Sydney) jumped from 38,523 in 2007 to 73,590 in 2007 and has remained at about this level since—a reflection of the sharp increase in the number of migrants holding temporary visas, mainly students, but also Working Holiday Migrants, 457 visa holders and visitors. In a similar pattern in Victoria migrant demography (NOM) increased from 39,561 in 2007 to 62,539 in 2007. Again, almost all of them chose to live in Melbourne.

So, for the most part this was not a revolving group. People are moving in faster than they are moving out of these cities.

Tens of thousands continue to stay on in Australia by switching to other temporary visas or by gaining permanent residence, through sponsorship by employers, by marriage, etc.

Australia's housing boom is no secret and has been going for 20 years. It has been more acute in recent years, with house prices across the country rising 40 per cent in the past five years — Brendan Coates

Two aspects of household numbers and distribution in Sydney and Melbourne stand out.

- A relatively large number of households in the 25–34 and 35–44 aged cohort has existed for a while; implying a bigger demand for detached housing in the near future. This is because most of these cohorts will already have started raising a family or will begin doing so at some point over the years to 2022.

- There will also be enormous growth in the number of households where the householder is aged 45 or more years. Most of these will be downsizing to couple households as their children leave home. Or, single person households as one or other of the partners die or move into aged care or need further help as their health may deteriorate. The main consequence of this will be a large increase in the number of small households occupying mainly detached houses in both Sydney and Melbourne. Projections indicate that there will be an additional 110,000 households aged 45 plus living in Sydney by 2022 and 162,000 in Melbourne as compared with 2012.

Younger households will, therefore, confronts an unprecedented squeeze when entering the housing market in each city. On the other hand, each additional occupancy due to ageing will mean one less of the stock of detached houses in Sydney and Melbourne that will be available to younger households including young residents and migrants.

Source: (CEDA, 2015) The housing affordability crisis in Sydney and Melbourne Report One: The demographic foundations

The CEDA report acknowledged an increasing percentage of Australians would become lifetime renters, and it recommended changes to laws governing lease agreements. ‘We need to have ten-year agreements or five-year agreements,’ Professor Maddock said. He believes greater certainty of tenure would ultimately benefit both renters and landlords. ‘But also, if you are an institution like a superannuation fund, you'll actually know that you've got five or ten years guaranteed rent.’

The younger generation of Australians has to appreciate a good proportion of them will not become homeowners in their lifetime; they probably will be permanent renters —Terry Burke

The number of Australian homeowners has been falling for three decades. Independent think tank, the Grattan Institute, analysed census data and found home ownership was declining among people aged under 55. It has prompted warnings that many young Australians are destined to be ‘permanent renters’. In 1986, 58 per cent of 25 to 34-year olds owned their home. That number is now 45 per cent, and the drop has been particularly dramatic in the last decade. According to Brendan Coates, a fellow at the Grattan Institute:

That might have been written off as a result of the delay in household formation—people are getting married and starting families later, so they're buying homes late—but we see the same trends amongst older age groups as well… Ownership in the 35–44 and 45–54 age groups has also fallen over the same period…What these numbers show is that there's clearly a problem linked to housing affordability. It shows we have a really big problem in ensuring the younger generations can afford to purchase a home.

Australia needs to build in more than 230,000 homes every year if we are to address our current housing affordability challenge—Tim Reardon

Build, Buy or Bust?

Terry Burke, a professor of housing studies at Swinburne University, agrees that the drop in home ownership, would have far-reaching consequences.

The younger generation of Australians has to appreciate a good proportion of them will not become homeowners in their lifetime, they probably will be permanent renters," he said. For example, in 1981, the median mortgage for 25-34-year-olds was only 17 per cent of their household income, but by 2011 that was already 25 per cent. They borrowed a lot more to achieve a similar home purchase than their parents would have 20 or 30 years ago…Back in the 60s and 70s and 80s you didn't have to have a dual income to become a home purchaser, now it's virtually an essential requirement.

Effectively having to invest a lot more money than their parents did, at a lower value return. This is an intergenerational issue where many younger households, the millennial generation, are unable to access home ownership or can only afford to buy in regions where house price growth generally has been more constrained. This means they do not have the same opportunities to accumulate housing wealth as earlier generations, such as the baby-boomers, many of whom have experienced massive increases in wealth as a result of rising housing prices

The housing affordability crisis could be widening the gap between rich and poor.

In a joint study conducted by University of Melbourne, University of Adelaide and University of South Australia conducted by Professor Bentley, found that housing unaffordability is driving people into a spiral of disadvantage.

People are moving to areas with less opportunity to get a good job and change or improve their situation. So, there’s a structural barrier for people to get a good job that could potentially get them out of their housing affordability problems…[This trend] also describes, potentially, a process of segregation, where people are getting sorted into less advantaged or more advantaged areas depending on the cost of the housing they can afford.

Source: HIA Economics

The study concludes that housing affordability was the key driver of the selective migration of some Australians into less advantaged places.

People need to be through employment to get better housing so they don’t keep moving to areas where they are less likely to get employment.

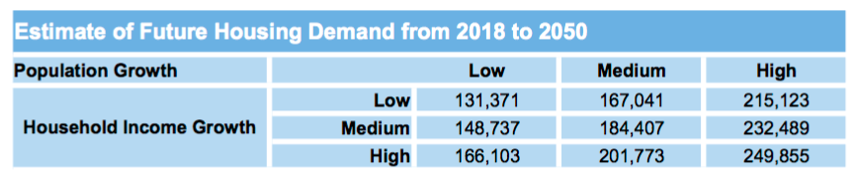

The Housing Australia report concluded that the demand pressures and supply problems were set to continue for the foreseeable future in Australia. ‘Barring any major economic jolts, demand pressures are likely to continue over the next 40 years and supply constraints will continue,’ CEDA said.

‘This is particularly the case in the capital cities where the growing population will increase the proportion of Australia's population to reside.’

CEDA discusses eight recommendations to improve Australia's housing affordability:

Prioritise shelter for most disadvantaged

Increase housing density by relaxing planning restrictions

Make planning, funding for transport infrastructure consistent

Provide adequate legal protection, certainty for long-term renters

Improve incentives to downsize to free up more land for development

Replace stamp duty with an annual land tax

Review pension, superannuation asset tests for housing

Increase capital gains tax to make investment less attractive

REFERENCES

Birrell, B., & McCloskey, D. (2015). The housing affordability crisis in Sydney and Melbourne Report One: The demographic foundations. The Australian Population Research Institute.

Chalkley-Rhoden, S. (2017 July 17) Home ownership in Australia in decline for three decades: Grattan Institute Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-07-17/home-ownership-in-australia-declines-for-decades/8677190

Kane A., (2015 Nov 13). Sydney and Melbourne are “building the wrong thing” Retrieved from https://www.thefifthestate.com.au/urbanism/planning/sydney-and-melbourne-are-building-the-wrong-thing-2/78466

Noone Y. (2017, Nov 23) Why the housing affordability crisis is making the poor even poorer Retrieved from https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/life/culture/article/2016/06/21/why-housing-affordability-crisis-making-poor-even-poorer

Stayner G. (2017 Aug 29) Housing affordability woes will continue for decades without major overhaul, CEDA says Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-29/housing-affordability-crisis-to-continue-for-decades-ceda-says/8851560

Written by: Nandini Sengupta (Freelance Urban Community Writer)